Sos – the Irish word for a break/pause. Sometimes a pause stretches out until it becomes an ending and this is one of those times. If you followed this blog when it was active, thank-you for being part of it. If you’ve randomly wandered in only to find it dormant I hope you find something interesting to read in our previous posts. Here are some of the most popular ones:

2B or not 2B

B, 2B, 3B, 5B, 8B, any old B please, as long as it’s not HB. And, shiver me pencil case, never 2H or 6H or HH. What am I on about? Pencils.

In pencil parlance the H family are HARD, and get harder as the number rises. H’s are good for writing and fine work like making architectural plans and technical drawings. The lovely soft B family are best for drawing. B stands for BLACK and the B leads get blacker (and softer) as they go up the number scale. Let me introduce you to some of the Bs.

A selection of Bs – perhaps B, 2B, 4B and 6B – will be the best thing you can provide for the ‘drawers’ in your family/classroom/library. You’ll find soft B pencils of some brand or other right there beside the hard Hs in any stationery/office supplies/art shop and they can be bought in packs of 12. You also need to provide your little artists with endless drawing paper. Buy sheets in packs – much cheaper than artist’s pads – but get drawing quality cartridge paper, NOT photocopy paper. Photocopy paper should only be used in art emergencies; it shouldn’t be your go-to drawing paper – it hasn’t got good ‘tooth’. It’s the paper equivalent of using margarine instead of butter. A pack of 100 A3 sheets of cartridge paper is about €3.55 in art supply stores, a ream (500 sheets) is about €13. Go large. A4 is a squashed, mean size for kids who are only getting their motor skills in gear and their creative juices flowing. A3 is a good size of paper and will fit on desks, A2 is an invitation to hit the floor and go wild.

Happy drawing!

This post is especially for the students at Marino Institute of Education. (MIE) is an associated college of Trinity College, Dublin, the University of Dublin. This is my third year as writer-in-residence.

TECHNICAL NOTE: Pencils behave very differently on different paper surfaces. Also pencil leads differ from manufacturer to manufacturer so that one maker’s 4B will be softer and darker than another’s – the ones in the photos are a bunch of Faber Castell ones we bought for using with participants at the draw along workshops we do. The H/F/B system of grading leads is used by UK/European and some USA pencil makers. Some USA manufacturers use #/numbers so #1 = B, #2 = HB and #4 =2H. Learn more about pencils here.

A #Bold Girl Learns to read

I was a slow reader. I couldn’t learn the ABC and my progress through the Peter and Jane readers was painful. I dreaded when my turn came to read in class; I stuttered and stumbled trying to make out those little black marks. My teacher thought I was lazy but even when I learnt the letters they stayed stubbornly separate; they would not form words inside my head. I remember the shame and panic, frowning and frowning at my allotted sentence as the whole class – fifty kids – waited. Once, I thought I recognised something.

‘Peter… saw, ’ I said triumphantly. I was sent straight to the corner to face the wall.

Not saw, bold girl! Was.

Towards the end of the school year I’d turned seven and was still making no progress. One day Miss Farrelly held up a book. It was thick, like a novel. It was dark blue. There was a wizard on the cover. A wizard!

‘This,’ Miss Farrelly said, ‘is a book for advanced readers. Those of you who find Peter and Jane too easy may buy it. If your parents wish you to have it they should send in three shillings and sixpence tomorrow.’

I wanted that book. I wanted it badly. I went home and told my mother there was a book to buy and I needed 3/6.

‘But you can’t read,’ Mam said.

‘Please, please,’ I said. ‘I’ll read it, I promise.’

‘If you don’t read it, it will be a waste of money,’ Mam said.

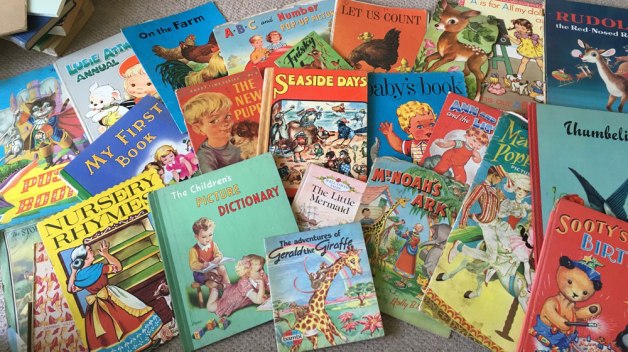

Now, my parents were book people. They saw books as necessities, like food and shoes. My sisters and I grew up surrounded by books. Here are some of the beautiful picturebooks we had as children:

But Mam hated waste. It took some persuading but the next day I marched up to Miss Farrelly, coins in hand.

‘This book is for advanced readers,’ she snapped. ‘You can’t even read.’

‘Mammy said I was to get it,’ I said.

Miss Farrelly rolled her eyes and tut-tutted but she handed over the book.

At home that afternoon I pulled the precious thing from my schoolbag and opened it. The letters sat there, black and unyielding. My joy turned to horror. Mammy would kill me! Mrs Farrelly would say she told me so. I looked at the first page. There was a lovely illustration of a dog and a fisherman. I was full of terror but also full of longing. I wanted in, wanted into the story.

Sandy… the… Sailor… Dog… said the title. A half hour later I realised I was three stories into the book. I was reading, reading fluently, gobbling words, turning pages. Something magical had happened; some switch inside my head had flipped. I was a reader.

This is a piece I wrote for #BOLD GIRLS. BOLD GIRLS is a Children’s Books Ireland initiative to mark the centenary of women’s suffrage in Ireland. It’s a celebration of brave, adventurous, curious and feisty girls and women in children’s literature, past and present. You can find info on the FEATURED AUTHORS AND ILLUSTRATORS, the BOLD GIRL READING GUIDE and the SCHOOL RESOURCE PACK HERE.

NOTE: Miss Farrelly was a stern teacher but who wouldn’t be, faced with 50 kids? She lived nearby and always had a hello and a smile for me as I passed from child to teen to adult. In ‘real life’ she had a twinkle in her eye and a hearty chuckle.

Murals with PJ Lynch

As part of his Laureate na nÓg Big Picture project, my good pal and birthday bud, PJ Lynch took on the task of organising SIX permanent murals (or muriels, as we say in Dublin) for a school in Cork, the very lovely Gaelscoil Mhainistir na Corann in Midleton. He invited Niamh Sharkey, Chris Judge, Lauren O’Neill, Michael and myself to join him and each take on a wall. Here are some photos of each mural as it happened, from blank to finished – click on the first photo to get larger images and some notes on what’s happening. Then keep clicking right.

PJ’s wall; The Children of Lir

Niamh’s wall; the King of Ireland

Lauren’s wall; Gulliver in Lilliput

Chris’s wall; Irish Creatures, Past & Present

My wall; image from The Long March

The school requested an image from my book The Long March (see two previous blogposts) as Midleton is home to the Feathers sculpture which commemorates the Choctaw gift to Ireland in 1847.

The whole team -Niamh Sharkey, Chris Judge, Jenny Murray (CBI), Lauren O’Neill, me, Aingeala (L na nÓg project manager), PJ Lynch – Laureate na nÓg.

Aingeala and Jenny looked after us so well (of course) and the school laid on a constant supply of sandwiches and scones and smiles and encouragement plus a laughter-filled night with the teachers at Muinteoir Gráinne’s on Saturday night. Unfortunately Michael was sick – whooping cough – and missed the trip, but he will tackle a wall for the school in May or June. We’ll add photos then.

Top photo of Niamh and myself beginning our murals is one PJ quietly snapped from the return of the stairs.

Rules for Researching (learned on the fly) -The Long March, part 2

Here are some of the rules I worked out about writing a book set in another time, place or culture when I was working on The Long March:

Ask every question at least twice; you may get different answers.

As described in my last blog I arrived in Oklahoma to research The Long March with a very rough first dummy under my oxter. The main character in that early version was a Choctaw boy but he spoke English; he was called Tobias, he wore European clothes and lived in a typical American log cabin. ‘Tobias’ was a result of the small amount of research I’d managed to do from Dublin via letter and fax (it was 1995) with a Choctaw contact I’d been given. When I was told the Choctaw would have had American/European names, clothes, houses in the 1840s I was startled, but accepted that if my contact said that’s how things were, then that’s how I had to portray them in my book.

After a week in Oklahoma everything changed. Now I knew my main character would have had two names: a Choctaw name plus a European name for the missionaries who lived amongst the tribe. I knew he and his family dressed in traditional Choctaw dress, with some European influences. I knew he lived in a log cabin but one without windows, as the Choctaw only used them for sleeping and storing. I knew Choctaw was his first language, and he had a maternal uncle, a moshi, who took the lead in disciplining and teaching him. I discovered all these things through conversations with Choctaw artist, writer and historian Gary White Deer, and other historians and archaeologists I met through him.

So why had my first contact told me that the Choctaw were fully europeanised in 1847? Were they mistaken? No. They were simply describing the past as it had been for their family.

The Choctaw lived side by side with Europeans for a century or so before being removed to Indian Territory (modern day Oklahoma). Some intermarried and many did business with the French and the English, and the Choctaw occasionally fought alongside the French in their disputes. A few Choctaw even owned land and slaves, but these were a tiny minority. In 1847 most of the people who had endured the removal from Mississippi and Alabama to Indian Territory were still living in the traditional Choctaw way.

Mind the Gap.

We all carry preconceptions. In 1995 I was full of them – things which had to do with my being Irish, European, white, female, a twentieth century human. No doubt I’m still full of them but I wasn’t aware enough then to know how they might blind me into adding erroneous details to the story and images. Some were glaring mistakes: in that first dummy I built a fence around the boy’s cabin. Fences are part of European culture, not Native American. Some errors were more nuanced: I had the Choctaw argue vehemently back and forth about sending money to Ireland, as if they were Irish folk relishing a good old barney. The Choctaw would have seen such arguing as rude. They’d have spoken politely at the meeting but ultimately acted however they saw fit. Luckily for me Choctaw historian, Gary White Deer, generously gave me his time and knowledge, picking up my mistakes and misconceptions. He showed them clearly to me as I wrote, rewrote, and sketched, sketched again, doing so much editing work that he is credited as such in the book. I couldn’t have made it without him.

Original, historic research is only as reliable as the source.

There is always a distinct possibility (probability, even) of bias with original recorders of events and culture (primary sources), but sometimes people are just sloppy. In the 19th century, several artists travelled across America drawing and painting the First Nations and Gary and Marshall Gettys suggested their work as a great resource. They both particularly recommended the paintings of George Catlin but warned me that he had a habit of adding details to images, such as random tepees and feathers because his clients in New York and Europe liked them (the Choctaw never used tepees and wore few feathers). He also tended to redraw images, occasionally flipping them. So, in the drawings below, the baldric (beaded sash) is shown worn correctly in the left image and incorrectly in the flipped image.

‘Never fall in love with your research’.

I’d heard Morgan Llywelyn say this a few years before at a conference and I came to understand exactly what she meant while working on this book. As I researched I found lots of little details and stories, some of which nestled nicely into my story, adding to it. However, I also caught myself trying to shoehorn in favourite facts just because, well, I wanted to. In the end I saw that they were pointless padding, cluttering up the narrative, and I duly ‘killed my darlings’. But ultimately I think none of the research goes to waste. With The Long March and also my novels Timecatcher, Dark Warning and Hagwitch, I’ve noticed that it all seems to be there, invisible but present, sitting between the lines.

Cultural appropriation.

Would I attempt The Long March if the idea presented itself today instead of in 1994 when I had only two books to my name? Simple answer: no.

It was only naiveté that let me think writing and illustrating a book about another culture would be difficult but do-able. Even though The Long March tells of an actual event which connects the Choctaw culture to mine I think the answer is still no; I might approach it from an Irish perspective instead, write it as an Irish immigrant observing from the outside perhaps. Today I’m too aware of the potential pitfalls and of the wholly valid arguments against attempting to write from inside another culture. At the time, as the enormity of what I’d taken on finally dawned on me, there came a point when I’d have given up on the book if Gary hadn’t been there to stop me making a mess of it. At the time I wrote and illustrated it I thought it would only be published in Ireland. It would have been tempting (but inexcusable) to think that the story of the gift was the important thing and the details of Choctaw culture didn’t matter so much in a book only available here. Ultimately the book was published in the USA and has had a long life there; longer than in Ireland. It was also published in Korea.

Though I wouldn’t attempt it now I loved making The Long March. I learned so much, about the Choctaw, about the Irish Famine, about myself, my cultural blindness and misconceptions; I developed my writing craft, I stretched myself artistically, I got to grips with the joys and hazards of research. In the end I wanted to get it right and serve the story of this amazing connection between the Choctaw and Ireland. And in the end I think that’s all any storyteller can do when they create a story set in another place or time.

Researching The Long March – part 1

The Dallas gas station was deserted. It was dark and I was too tired from travelling to register anything unusual. Gary filled up the tank and walked inside the shop to pay, but almost immediately hurried back to the car. ‘There’s been a hold up,’ he said. ‘The teller is hiding behind the counter and she screamed at me to get out. I asked her if she wanted me to stay till the cops arrive but she kept yelling at me to go away.’ He turned the key and pulled out onto the street.

I had come to the US to research a picturebook called The Long March. It would tell the story of the aid the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma had sent to Ireland during the worst year of the Great Famine. Gary Whitedeer and his wife Sarah had kindly driven to Dallas airport to pick me up and bring me to my hotel in Oklahoma. As we crossed the vast state of Texas I nodded off in the back seat. An hour later, I woke with a start. The car had pulled over; through the side window I made out a pair of hips, a gun in a holster. Gary had been stopped for speeding. It was 1995; I was only a few hours into my first ever trip to the USA and so far the USA was doing its damnedest to live up to my Irish preconceptions. But in the following week, as I gathered the information for my book, I would see an America most Irish tourists never see.

The spark for The Long March began with hearing Don Mullan on the radio speaking about the money the Choctaw sent to Ireland in 1847. I’d never heard the story before but I immediately figured it would make a great picturebook, and contacted Don. He gave me all the information he had and some names and addresses in Oklahoma. The World Wide Web was in its infancy then so my first attempts at research were by fax, letter and phone. After a year or so of trying to gather information from a distance I came to realise I needed to travel to Oklahoma and do some proper research on the ground. At the time Aer Lingus offered free flights to writers and artists who could show they had an artistic need to fly. (I know! Imagine! That was actually a thing!) With Don’s help I put out feelers and the office of the Chief of the Choctaw Nation extended me an invitation to stay in their hotel at Arrowhead. Gary and Sarah dropped me there in the wee hours. I was shown to a suite(!) and fell exhausted onto my first ever king-sized bed. Next morning I woke up to find myself in a huge space with gigantic glass windows, looking out over Lake Eufaula.

I had a week to find out everything I could about the Choctaw – what they wore, how they lived back in 1847. I intended to illustrate this book in a realistic style so I also needed to find models for the main characters and take photos of them. I had no idea how was I going to do any of this. As an Irish person used to being near bus and train stops, I hadn’t understood how isolated things in the US can be. Without a car I was basically marooned in a big hotel. I was still an L driver in 1995 but even if I’d been able to hire a car I hadn’t the first clue where I needed to go or who I needed to see. I really hadn’t thought this through…

Gary and Sarah (who is Kiowa) came to my rescue. One or both arrived every day and drove me to meet people they thought could help me: Marshall Gettys, historian and collector, showed me around his own personal collection of First Nation baskets, tools and implements, pointing out the Choctaw items; an archaeologist called Butch talked me through the type of houses the Choctaw lived in, mid 19th century. Both men agreed to send me photocopies of photos, drawings and articles.

Sarah brought me to an old meeting-house one day and Gary brought me to meet his aunts and cousins, folk who had grown up using Choctaw as their first language. Gary’s aunt, Lena Noah, had an incredibly beautiful face and I instantly knew that I would replace the old man character of my first draft with a grandmother figure, just as I knew when I met Gary and Sarah’s son Quanah that I would change my main character from a ten-year-old to an early teen.

On long car journeys I asked questions and listened carefully to the answers. In the evening back in my suite I wrote copious notes while stunning electrical storms flashed over the lake outside. The more I learned, the more obvious it was how little I knew and what a daft, naïve and downright arrogant idea doing this book about another culture was. But it seemed too late to pull out now when the Choctaw Nation offices and so many people – Gary and Sarah in particular – were giving so generously of their time, knowledge and energy.

I only spent a week in Oklahoma but it felt like a month because it was packed with new experiences. With the help of the Choctaw Nation offices I met a gang of Choctaw teenagers at their youth club and I went to a craft show in the Choctaw Community Centre. I spent time hanging out at Gary and Sarah’s, taking photos of their kids and of the traditional arbour Gary had built in their yard. I saw some lovely scenery and miles and miles of highway as people drove me long distances across Oklahoma. There was a sign near the state penitentiary which I particularly liked; it said: Motorists, Beware! Hitchhikers May Be Escaping Convicts. One night I stayed in a motel right out of film noir – The Indian Hillside.

‘Don’t know why they call it that,’ Gary said. ‘No Indians; no hillside.’ As he dropped me at the office, he laughed. ‘Oh look,’ he said. ‘Real Indians.’ The guys in the office were from Delhi.

The rain poured down and an old man in flowery boxer shorts stood in the doorway of his room shouting, Hello! Hello! Hello! as I struggled to unlock my door. The motel room was brown, grimy and 100% nylon. Thunder and lightning raged all night while I wondered about the dark stains on the carpet and walls. I was glad to return to my pristine suite! I had by now realised that Arrowhead Hotel was a casino specialising in high stakes bingo, which explained why there were so many old folks staying there.

By the end of the week I’d shot a couple of hundred photos (rolls of film), catching faces and places I thought I might use in my book. When I left Oklahoma I travelled on to stay with friends in Philly and New York and took a Greyhound bus to visit the Smithsonian museums in Washington – The Long March would be named a Smithsonian Notable Book in 1998 – but my best memories, my strongest memories, come from that first week with the Choctaw. And my favourite memory of all is of the night Gary and Sarah and their kids brought me to a dance at the Kulli Homa dance grounds.

A small number of Choctaw and Chickasaw families gathered in a clearing in the woods. We ate cornbread and chicken, and dumplings in grape juice. A fire cackled in the middle of the circle and the women and girls sat to the right of it, men and boys to the left. Gary, drumming on an Irish bodhrán, walked into the centre to call the dances. The men formed a line behind him. As they approached our side of the circle the women rose and threaded themselves between the men.

I didn’t join in right away; I waited to be invited. I danced Duck Dance and Snake Dance and Friendship Dance. I tried to stay towards the back of the line and watch and learn. I noticed that when a dance ended, the dancers made sure to finish the anti-clockwise revolution of the fire, never backtracking to return to their seats. I did the same. Some of the Chickasaw girls were wearing shell-shakers on their legs which made noise as they stomped. The modern ones were cylinders formed from cans filled with dried beans but one girl was wearing an old pair made of many turtle shells. She put them on my legs so I could feel how heavy they were.

I didn’t join in right away; I waited to be invited. I danced Duck Dance and Snake Dance and Friendship Dance. I tried to stay towards the back of the line and watch and learn. I noticed that when a dance ended, the dancers made sure to finish the anti-clockwise revolution of the fire, never backtracking to return to their seats. I did the same. Some of the Chickasaw girls were wearing shell-shakers on their legs which made noise as they stomped. The modern ones were cylinders formed from cans filled with dried beans but one girl was wearing an old pair made of many turtle shells. She put them on my legs so I could feel how heavy they were.

The racket of the cicadas in the woods was incredible. The sky was full of stars. I heard my first whippoorwill that night, saw my first fireflies. A child caught some of the little insects in a jar so I could see them up close. I remember thinking to myself, ‘be here now. Don’t think forwards or backwards; be in this moment,’ and today I can still conjure that far-off hot July evening, if I close my eyes.

This is the first of three blogs on making of my picture book, The Long March. It was published in 1998. The Long March tells the story of the gift of money which the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma sent to Ireland as aid during the worst year of the Great Famine –1847. The next blog will be about the pitfalls, mistakes and discoveries which may occur when researching a book set in another time and place. The third will look at the visual sources needed to create a single image.

Taking Criticism

For a writer taking criticism of your work is part of the job but it’s difficult not to be devastated by some of the things editors say – or don’t say. When I do critiques for aspiring writers I’m very conscious of this. I try to couch my opinion in a gentle way but that can mean I’m not being honest or clear, so now instead of beating around the bush I preface with some advice on how to approach feedback:

This is probably the first critique of your work you have ever received so you should know that ALL writers (no matter how long they’ve been writing) tend to hone in immediately on the negative remarks in critiques and ignore the positive; I know I do. Having your work critiqued can feel a little like being flattened by a steamroller! Read on, but remember good writing is all about teasing out what’s working and what isn’t, and then rewriting/editing with that in mind. Whether it’s song lyrics, poetry or prose, no one writes perfect ready-to-publish pieces straight from their head onto the page. All ‘mistakes’ are there to be learnt from and are the typical mistakes everyone makes when starting out. If you pick up any of the books on writing I recommend you’ll see they all cover the same ground over and over again. Writing is a craft as well as an art and this critique is about helping you develop the craft. Most writers write, rewrite, rewrite and rewrite again. First drafts are just that – drafts. When I critique work I intend everything to be taken positively. Everything is about going forward to the next stage.

Then comes the critique. At the end I add some advice on how to recover from it:

Picking yourself up after a crit of your work –

Having your work critiqued can be overwhelming and feel very negative. This is how I respond to having my work pulled apart by editors.

- I go into a 24 hour sulk and eat chocolate cake.

- Then I acknowledge to myself that there are things in the crit which hit me in the gut as true. These are things I know in my heart I need to fix.

- Conversely there is usually at least one thing in a crit/edit which I don’t connect with at all, something which feels wrong/incorrect – I examine these but ignore anything which honestly feels wrong or as if the editor didn’t ‘get’ something.

- I may continue to feel irritated and sulky but I accept there is work to be done, usually way more than I thought.

- I take a few days, a few weeks or a few months away from the work to absorb this and to put some distance between myself and the manuscript. When I pick it back up and reread I can usually see lots of stuff that needs doing and can now attack it with energy and purpose.

- Editing and rewriting can feel daunting and a chore but when you actually get into it and see your work get tighter and cleaner and better you should begin to enjoy it.

The yellow image above is one of four pages of feedback from my editor on the first draft of the opening six chapters of my first novel. The blue image is the first page of feedback on draft number four. Note that this sheet only covers the problems on pages 1-37! The scribbles are my reactions to the notes. I was lucky to have a fine editor holding my hand through the process of writing Timecatcher and I learnt a huge amount about the writing craft from him.

To the students of Marino Institute of Education: Three brave Marino students have already sent me work to critique and I enjoyed reading their manuscripts very much. I hope my feedback was useful and they had cake to hand when reading it. I’m up for critiquing three more pieces, so if you are a secret writer or illustrator send me one chapter or some images or a handful of poems or a short story or a picture book idea, but get them to Ciara Ní Bhroin ASAP as it will be on a first come, first served basis.

Rudolph’s First Christmas

We wish you Season’s Greetings with a repost of Michael telling the story of how Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer came to be in 1939. Michael has a personal connection with the little reindeer – he illustrated the official version in 1994.

Cover of 1994 publication illustrated by Michael. This edition is no longer in print. ©Robert L.May Company

Bob fidgeted in his oak office chair. He glanced up from his typewriter at the clock on the wall. 3PM. Two more hours and he could leave. The holidays had just come and gone, but the usual joyous event had been celebrated under a cloud.

The papers that year were full of bad news. A massive war looked likely again in Europe. Germany’s new fascist leader Adolf Hitler had just announced in parliament his plan to exterminate all European Jews. Bob and his wife Evelyn were both Jewish. Germany would soon march its rebuilt army through Vienna, Prague and then into Poland, killing thousands of people on its way. Russia had invaded Finland, Franco’s Fascists had taken over the government in Spain. Britain was arming for war. America was watching nervously.

Bob wanted to get a something nice for his wife, who was terribly ill with cancer. It was snowing outside on the streets of Chicago, but working for Montgomery Ward, one of the biggest department stores in the city, he could shop by taking the stairs up to the ladies department without going outside.

Bob glanced at the clock again. 4PM. One more hour. He hit two keys at once and his typewriter jammed. He cursed just as a bell rang and he was called to the phone. He crossed the room, wiping deep blue ink from his fingers as best he could before he picking up the inter office line.

“Bob? How’s it going? Not busy are you? Good. Listen, gotta job for you. Boss wants to get started on this year’s Christmas campaign early. Macy’s is killing us. He wants a promo piece, yeah, something for the kiddies. Something happy. Uh huh, ‘first 200 customers through the door gets one free’ kinda thing.”

Bob glanced at the clock again – 4:45.

“Nope. Boss wants you. You’re always doing those funny little poems. And Bob, the boss wants to see some ideas tomorrow. Christmas will be here again before you know it. You on it? All right. See you, 9AM, sharp.”

It was already dark outside, the holiday lights still up, blazing in the store windows, gathering crowds of post-holiday shoppers. But deep in the basement offices of the advertising department of Montgomery Ward department store, there were no windows. Just the glow of a green desk lamp.

Slumped at his desk, Bob aimlessly sharpened a pencil with his pocket knife. How was he supposed to work on something happy for kids with all the madness going on in the world?

He tried to focus. Other young Jewish American artists at that time, also engrossed by the horrors unfolding across Europe, were creating new kinds of superheros – comics artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger created Batman the same year, writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster created Superman just the year before.

But Bob would invent his own, quieter character. Small, persecuted, an outsider – one of Santa’s reindeer. A little deer with a big nose – an all too common antisemitic caricature of the time. Rudolph. Rudy the Red-nose. Bob began to type, typed some more. The nose became the key to the story. Soon the clock showed 2AM. But he’d done it. He had his hero.

It’s impossible to know the exact genesis of any creative idea. But some facts are clear, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was undoubtedly born on a dark day in January, 1939, in the mind of Robert L. May, at a small desk in the advertising department of the Montgomery Ward store in Chicago, amid very personal, unimaginable grief and inescapable daily accounts of inhuman global turmoil, cruelty and suffering.

It’s impossible to know the exact genesis of any creative idea. But some facts are clear, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer was undoubtedly born on a dark day in January, 1939, in the mind of Robert L. May, at a small desk in the advertising department of the Montgomery Ward store in Chicago, amid very personal, unimaginable grief and inescapable daily accounts of inhuman global turmoil, cruelty and suffering.

Sadly, before the work was completed, Robert L May’s wife Evelyn died. Robert was told he needn’t finish the project but he chose to work through his grief, eventually completing it in August of that year. The rhyming poem was an instant hit. 2.4 million copies were given away during Christmas 1939. The hopeful tale of a plucky little deer with the big red nose was just the antidote to the gloom of world events.

The little book slept during the war because of paper shortages. Then after the war, another 3.5 million were printed. In 1946 Robert asked his boss if he could have the rights to Rudolph. In an act of unusual generosity, his boss agreed.

A few years later, Bob’s brother-in-law, a struggling songwriter named Johnny Marks, proposed writing a song about Rudolph. He was convinced it would boost Rudolph’s name around the world. He was right. The song was indeed a hit, becoming the best-selling record in America for over 30 years. The May and Marks families have been caretakers of Rudolph ever since – almost 80 years. The two families need to agree on most projects, deciding what is best for the famous little deer, who is practically part of the family.

I personally became involved in Rudolph’s world when a local Boston area publisher, specializing in quality reproductions of historical literature, Applewood Books, contacted me to illustrate a second, less known and never fully illustrated story about Rudolph, titled Rudolph’s Second Christmas. They had already reprinted an exclusive edition of the first book with the original illustrations by Montgomery Ward staff artist Denver Gillen, with great success.

I met Robert May’s daughter, who at the time was managing the family Rudolph business. She told me 99% of her job involved chasing bootleggers who were using Rudolph’s image to make illegal t-shirts, coffee cups and toys. Many of the Rudolph toys you see are actually black market contraband.

I agreed to illustrate the book, and its success led to a second book project, a new edition of the original story, Rudolph, The Red-nosed Reindeer. It was published in 1994. No, I didn’t get rich. I was paid a one-off fee. You never own anything relating to a licensed character. I’ll never see the art again but I knew this before I started.

I’ll never suggest I suffered the mental turmoil Robert did, but somehow it seemed fitting that the color work on the first book was completed with my drawing-hand in a cast (due to an untimely broken wrist), with the help of a good friend -a skilled artist- and a lot of painkillers. It was a rewarding experience overall, illustrating such an iconic character of American children’s literature. I grew up watching the beloved TV version. Too bad I didn’t get a chance to draw my favorite character from that animated version – one Robert L. May never imagined Rudolph would meet – the abominable snowman.

All illustrations by Michael Emberley © Robert L. May Company. Strictly copyright protected.

Learn About Bats!

I studied bats and owls quite a bit before beginning the finished art for Owl Bat Bat Owl. I pulled out books on the subject and sketched directly from photos to ‘learn’ them. By sketching from photographs I got a handle on bat wings and how they move.

In the book I’ve simplified the bats and I’m taking major artistic licence with the babies (bats have single pups – rarely twins, never three), but I like to begin with the real animal and how it moves and behaves. I prefer to consciously simplify/take artistic licence, rather than do stuff by mistake!

After a year drawing owls and bats for Owl Bat Bat Owl it seemed like serendipity when Bat Conservation Ireland got in touch to ask if I’d do some illustrations for a new website they were making called Learnaboutbats. I asked if I could use ‘my’ bats for the site. They said yes, and we were in business.

Making images for the website I discovered I still had plenty to learn about bats! Like all illustrators working to a brief I provide rough line drawings initially. This is so the client can spot mistakes and problems before I take the image to full-colour art.

There were loads of wee problems with my initial drawings. For instance I clustered sleeping bats together in a cave for the hibernation image. Mistake! Bats need to cool down to hibernate so they keep their distance from one another. The images of tightly packed bats I was referencing were of summertime roosting mums.

Myself and Niamh Roche at Bat Conservation Ireland emailed back and forth until I had the details right, then I went to colour. The site went live in October and you can fly over to learnaboutbats.com for lots of wonderful Bat Facts.

Myself and Niamh Roche at Bat Conservation Ireland emailed back and forth until I had the details right, then I went to colour. The site went live in October and you can fly over to learnaboutbats.com for lots of wonderful Bat Facts.

There’s info on Irish bats, on a year in the life of a bat, and a slide presentation that will be great for use in the classroom.

There are suggestions for games and activities too! https://www.learnaboutbats.com/fun-things-to-do/

Get clicking. https://www.learnaboutbats.com/

And there are t-shirts! Ours arrived in the post this week 🙂

The Book of Clondalkin

Nothing quite like drawing directly from a piece of celtic knotwork to reveal what exactly is hidden amongst all those swirls. The folk at Brú Chrónáin, the new centre at the Clondalkin Round Tower, asked me to design a logo for their tour guides. They suggested I use a detail from the remaining fragments of the Book of Clondalkin as a basis.

At first glance I could make out a bird and what seemed to be another bird with a crest, or some sort of dog-beast. It was when I was eyeballing the drawing and trying to redraw it that I realised the beast had hooves and a horn. Not a dog then; a unicorn! Drawing something, whether it’s a complex image or a living animal, makes you really examine it properly and helps you see the details.

The fragments, which are all that remain of the Book of Clondalkin, are kept in Karlsruhe Badische Landesbibliothek, Germany. You can see photos of the fragments when you visit Brú Chrónáin or check out some of it here Handschriften / Sacramentarium, Fragment – Aug. Fr. 18.